Today we have completed our final day of touring Canadian battlefields, before we move on to Amsterdam and our flight home. We have visited five European countries, and dozens of Commonwealth War Grave cemeteries, battlefields, and museums. We have consciously sought out most of these sights, plotting them on the map and judiciously following the GPS’s instructions. On this trip I was struck by the way that reminders of the First and Second World Wars were integrated into the landscape in every country we visited. If you began to look, visitors could see monument and plaques to the Canadians and other combatants, and landscapes and cities shaped by the battles fought in this part of Europe. The cities in Canada where most of us live do contain memorials to these conflicts, and the men who fought in them, but the landscape here was affected in a deeper way.

We have visited several memorials—Thiepval, Vimy Ridge, the Menin Gate—that were intended to draw people’s attention and be lasting reminders of the men who died in the World Wars. These sites attract thousands of visitors from many countries, and continue to focus student’s attention on the battles and sacrifices commemorated in these memorials. As we build the myth and memory of the wars, these international monuments serve as representations.

Other sites are more integrated into the towns and countryside, such as the cemeteries for the commonwealth soldiers, and the smaller plaques and memorials recognizing local battles. These sites are not as prominent in most narratives of the war, but they are places that Canadians, family members of the soldiers, and students like us to come and remember, mourn, and recognize those men who gave their lives during the World Wars. I was shocked by the sheer number of cemeteries, especially in the Somme region of the France where many of the dead were buried in the local trenches where they died, rather than being brought to a larger, more centralized location. There were many places in France where, as we stood on a ridge, we could see in the distance two, or even three CWGC cemeteries, which stand out from the scenery through their uniform swath of rounded, white headstones. We often hear of the number of men who died in the wars, but actually seeing so many individual graves, and individual names on monuments for those with no known grave, vividly demonstrated the huge loss of life during these wars.

The European countries we have been through also show remnants of war in more subtle ways. This area of Europe was a battlefield, and experienced the carnage and destruction of modern, mechanized warfare. The trench warfare of WWI in France created a pockmarked landscape that, where preserved at Beaumont Hamel or Vimy Ridge, shows the destruction of flat farmers’ fields into a series of craters. Initially, these would have been filled with mud, barbed wire, and the other detritus of war, but now they have been covered in soft green grass and tiny spring flowers, which creates a peaceful landscape at odds with the destruction it is evidence of. Similarly, today we visited Westerbork transit camp, where Dutch Jews were sent before they were shipped to concentration camps to the east. While the buildings of the site from the 1940s are no longer standing, there remain purposeful memorials to the Jews who departed from Westerbork, and grass-covered ridges mark where the building used to stand. The fields of France show similar unintentional signs of war, as the soil of farmers’ fields becomes gray and chalky in areas that used to contain the bunkers and trenches of WWI. Finally, many of the new building we have passed by and lived in, in cities that are centuries old, show where buildings were destroyed by the fighting, and have been entirely rebuilt within the last century.

These and other signs of the World Wars still dot the countryside and cities of France, Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, and those like us who seek them out see how the wars and their consequences can be remembered through the landscape of Europe.

Cindel White

After the hard-hitting, fast-paced nine days we’ve spent in Europe (which isn’t including the packed days we had in Ottawa), we actually had a bit of a “break” today, as we were not nearly as busy as we have been. This became a double-edged sword as I found myself wanting more, but really enjoyed the time to myself and spending it with my peers more casually in a foreign city.

After the hard-hitting, fast-paced nine days we’ve spent in Europe (which isn’t including the packed days we had in Ottawa), we actually had a bit of a “break” today, as we were not nearly as busy as we have been. This became a double-edged sword as I found myself wanting more, but really enjoyed the time to myself and spending it with my peers more casually in a foreign city. From here we made our way to the Arnhem-Oosterbeek War Cemetery, quite close to the actual museum. In this cemetery, over 1,700 individuals (from Poland, Canada, Britain, Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand) are buried here, most of which as a result from the Battle of Arnhem from September 1944, but also those killed in the region from September 1944-April 1945.

From here we made our way to the Arnhem-Oosterbeek War Cemetery, quite close to the actual museum. In this cemetery, over 1,700 individuals (from Poland, Canada, Britain, Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand) are buried here, most of which as a result from the Battle of Arnhem from September 1944, but also those killed in the region from September 1944-April 1945. the Battle of Arnhem more specifically. There seems to be no great consensus towards the role played by Arnhem civilians. Some monuments, plaques, and inscriptions appear to apologise for Arnhem civilians’ premature exuberance during the battle and getting in the way of Allied soldiers. Other such commemorative pieces applaud and encourage the inspirational zeal displayed by these civilians and their attempts to aid the Allied soldiers in whatever way they could. The excitement felt by civilians in the area, seeing not just Allied soldiers, but the culmination of their hopes and dreams for freedom was simply overwhelming as they wished to help in this process any way they could, naturally leading to a disruption in Allied maneuvers, however slight.

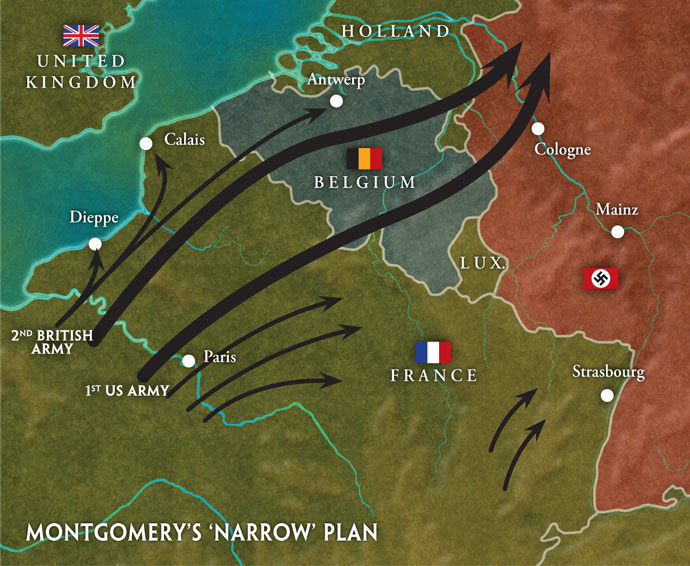

the Battle of Arnhem more specifically. There seems to be no great consensus towards the role played by Arnhem civilians. Some monuments, plaques, and inscriptions appear to apologise for Arnhem civilians’ premature exuberance during the battle and getting in the way of Allied soldiers. Other such commemorative pieces applaud and encourage the inspirational zeal displayed by these civilians and their attempts to aid the Allied soldiers in whatever way they could. The excitement felt by civilians in the area, seeing not just Allied soldiers, but the culmination of their hopes and dreams for freedom was simply overwhelming as they wished to help in this process any way they could, naturally leading to a disruption in Allied maneuvers, however slight. In order for the war to end by Christmas 1944, conditions had to be just about perfect for Montgomery’s single thrust strategy to work, leaving way too much up to chance. By attacking the (very long) German line in a single thrust, it simply leaves too much undefended space and open flanks to be effective. Especially with the heavily held and greatly defended German Siegfried Line barely southeast of their position, winning the war by Christmas would be living the dream.

In order for the war to end by Christmas 1944, conditions had to be just about perfect for Montgomery’s single thrust strategy to work, leaving way too much up to chance. By attacking the (very long) German line in a single thrust, it simply leaves too much undefended space and open flanks to be effective. Especially with the heavily held and greatly defended German Siegfried Line barely southeast of their position, winning the war by Christmas would be living the dream.