The Allied situation in the spring of 1942 was grim. The Germans had penetrated deep into Russia, the British Eighth Army in North Africa had been forced back into Egypt, and in Western Europe the Allied forces faced the Germans across the English Channel.

The Russians were demanding a Second Front – a full-scale invasion of Western Europe. Since the Allies had not the logistical power to mount an invasion, they decided to stage a major raid on the French port of Dieppe. Designed to foster German fears of an attack in the west, compelling them to strengthen their Channel defences at the expense of other areas of operation as well as to placate Stalin, the raid would also provide an opportunity to test new techniques and equipment, and be the means to gain the experience and knowledge necessary for planning the great amphibious assault.

The attack upon Dieppe took place on August 19, 1942. The troops involved totalled 6,100 of whom roughly 5,000 were Canadians, the remainder being British Commandos and 50 American Rangers. They had received extensive commando-type training earlier in the summer, when the first attempt had been cancelled at the last minute because of bad weather. The raid was supported by eight Allied destroyers and 74 Allied air squadrons (eight belonging to the Royal Canadian Air Force, RCAF).

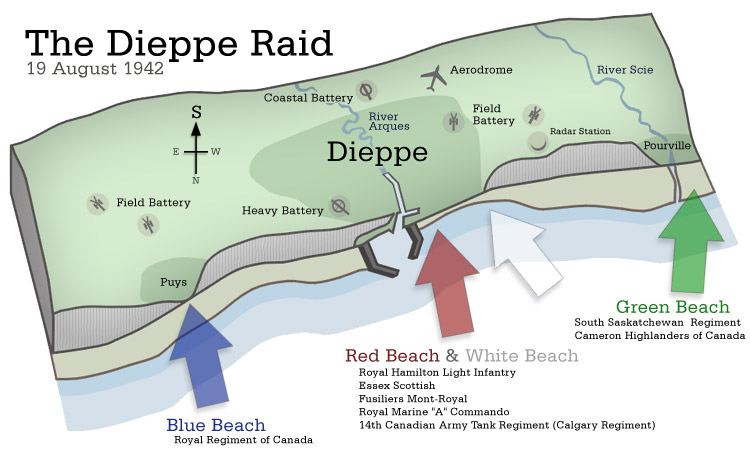

The plan called for attacks at five different points on a front of roughly 16 kilometres. Canadian forces would launch simultaneous flank attacks just before dawn on the cliffs east and west of the port (at Pourville and Puys), followed half an hour later by the main attack on the town of Dieppe itself. British commandos were assigned to destroy the coastal batteries at Berneval on the eastern flank, and at Varengeville in the west.

Success depended on surprise and darkness, neither of which prevailed, due to a series of mishaps. At Puys, on the eastern flank, the Royal Regiment of Canada met violent machine-gun fire from the fully-alerted German soldiers. The troops, together with three platoons of reinforcements from the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, were pinned on the beach by mortar and machine-gun fire, and were later forced to surrender. Evacuation was impossible in the face of German fire. Of those who landed, 200 were killed and 20 died later of their wounds; the rest were taken prisoner — the heaviest toll suffered by a Canadian battalion in a single day throughout the entire war. Failure to clear the eastern headland enabled the Germans to enfilade the Dieppe beaches and nullify the main frontal attack.

At Pourville, on the western flank, the South Saskatchewan Regiment and Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada also met stiff resistance and were forced to halt.

The main attack was to be made across the pebble beach in front of Dieppe. German soldiers, concealed in cliff top positions and in buildings overlooking the promenade, waited. As the men of the Essex Scottish Regiment assaulted the open eastern section, the enemy swept the beach with machine-gun fire. All attempts to breach the seawall were beaten back with grievous loss. When one small party managed to infiltrate the town, a misleading message was received aboard the headquarters ship, which suggested that the Essex Scottish were making headway. Thus, the reserve battalion Les Fusiliers Mont Royal was sent in. They, like their comrades who had landed earlier, found themselves pinned down on the beach and exposed to intense enemy fire.

The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry landed at the west end of the promenade opposite a large isolated casino. They were able to clear this strongly-held building and the nearby pillboxes and some men of the battalion got across the bullet-swept boulevard and into the town, where they were engaged in vicious street fighting.

Misfortune also attended the landing of the tanks of the Calgary Regiment. Timed to follow an air and naval bombardment, they were put ashore ten to fifteen minutes late, thus leaving the infantry without support during the first critical minutes of the attack. Then as the tanks came ashore, they met an inferno of fire and were brought to a halt, stopped not only by enemy guns, but also immobilized by the shingle banks and seawall. Those that negotiated the seawall found their way blocked by concrete obstacles, which sealed off the narrow streets. Nevertheless, the immobilized tanks continued to fight, supporting the infantry and contributing greatly to the withdrawal of many of them; the tank crews became prisoners or died in battle.

The last troops to land were part of the Royal Marine “A” Commando, who shared the terrible fate of the Canadians. They suffered heavy losses without being able to accomplish their mission.

The raid also produced the most tremendous air battle of the war. While the Allied air forces were able to provide protection from the Luftwaffe for the ships off Dieppe, the cost was high. The Royal Air Force lost 106 aircraft, which was to be the highest ever single-day total The RCAF loss was 13 aircraft.

By early afternoon, Operation Jubilee was over. Conflicting assessments of the value of the raid continue to be presented. Some claim that it was a useless slaughter; others maintain that it was necessary to the successful invasion of the continent two years later on D-Day. Out of it came improvements in technique, fire support and tactics, which reduced D-Day casualties to an unexpected minimum. The men who perished at Dieppe were instrumental in saving countless lives on June 6, 1944. While there can be no doubt that valuable lessons were learned, a frightful price was paid in those morning hours of August 19, 1942. Of the 4,963 Canadians who embarked for the operation only 2,210 returned to England, and many of these were wounded. There were 3,367 casualties, including 1,946 prisoners of war; 907 Canadians lost their lives.

Adapted from an account by historian Terry Copp, published in Legion Magazine