After five weeks of hard fighting and terrible casualties, the Allied forces were still penned in the anteroom of Normandy. Access to the broad Norman plains remained firmly blocked by the massive German firepower and armour.

After five weeks of hard fighting and terrible casualties, the Allied forces were still penned in the anteroom of Normandy. Access to the broad Norman plains remained firmly blocked by the massive German firepower and armour.

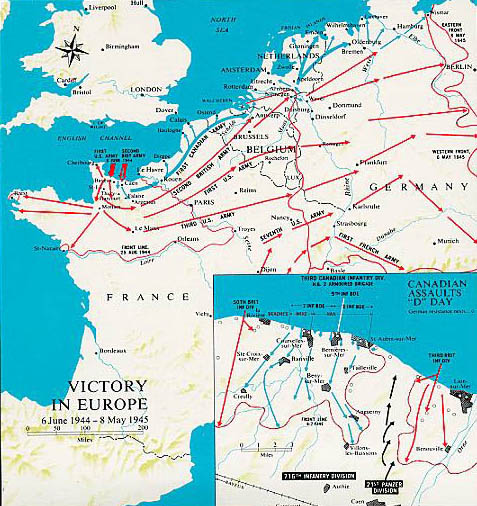

The original 176,000 Allied invaders had now burgeoned into a multinational force of more than a million men (despite the 122,000 killed or wounded). All forces were still contained within this ribbon of coastline some fifty miles long. The deepest penetration inland was 25 to 30 miles; in many places it was a mere five or six miles. Behind them was the English Channel; in front, the German army.

Crammed into this small space with them was massed undoubtedly the largest assembly of matériel in the history of modern warfare: tanks, armoured vehicles, fuel, weapons, ammunition, materials for bridging and for building airstrips; food, water and medical supplies for the troops. And the supplies were pouring in by the hour. Traffic jams of immense proportions were the norm.

General Bernard Montgomery’s break-out plan was two-fold. The Canadians and British at Caen, at the eastern end of the lodgment, would use all their resources to pin down and keep pinned down the might of seven of the nine German panzer divisions in Normandy. The illusion of an attack by Armée Gruppe Patton at the Pas de Calais was immobilizing still more German divisions east of the Seine.

The Americans at the western end of the confined area could therefore exert their ever-growing power to force an entry into the interior of Normandy against minimal panzeropposition. The build-up of American forces and matériel to achieve this was essential. French and Polish forces were preparing to join in support of the expanded invasion force.

But by D–plus-44 the reality seemed to be that Monty’s plan was not working. After the fall of Cherbourg on 26 June, the Americans turned the full weight of their army to the south. As they penetrated the enemy-held territory, they found the battleground as formidable as the enemy. The area between the U.S. sector on the coast south to St.-Lô – the area the Allies had to penetrate if they were to achieve a breakout – was twenty miles of dense, hilly hedgerow country. This was the bocage.

With ingenuity, sheer guts and incurring almost 100% casualties, the Americans gradually broke through the hostile country and burst out in August in a wide encircling sweep across Normandy, cutting northwards towards Falaise.

The British and Canadians meanwhile forged a line through the unyielding enemy panzerdefences by tortuous miles. By mid-August, the Canadians and Poles reached Falaise and St. Lambert-sur-Dives, where Major David Currie won his V.C.

Although the Americans were closing from the south, the Germans were left with a narrow escape gap. Nevertheless, 25,000 of the enemy were killed or captured and the German army was driven out of France. The Normandy Campaign cost the allies close to 2,500 casualties a day.

Adapted from Victory at Falaise by Denis & Shelagh Whitaker with Terry Copp

For more than a decade, the Canadian Battlefields Foundation has brought history to life for the senior university students it sponsors annually for two weeks’ of intensive touring and study in Europe. Under the guidance of distinguished Canadian historians, they walk in the footsteps of Canada’s military, visualizing their land, sea and air contributions in two world wars. Wilfrid Laurier MA History graduate John Maker observed:

“After seeing the ground, smelling the air and feeling the Norman sun, I have developed an even deeper respect and understanding for the excellent work done by our Canadian soldiers. This knowledge will be an invaluable asset in my future as a student of Canadian Military History. The Canadian Battlefields Foundation has done a wonderful thing for me and I appreciate it greatly… Keep it up!”